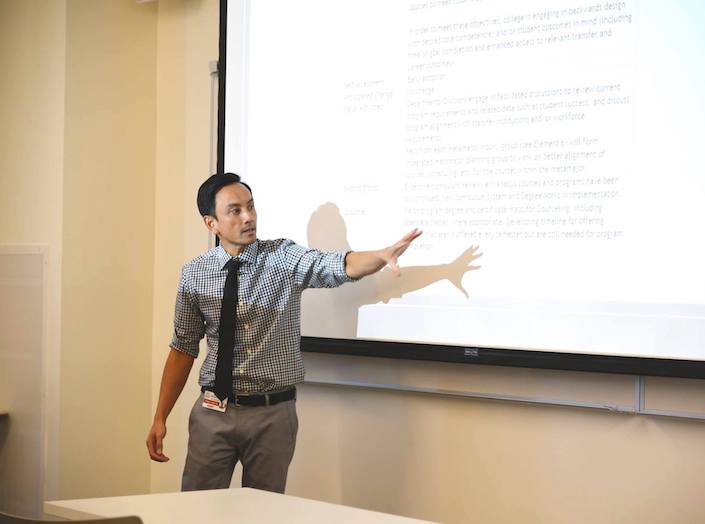

Danny Nguyen, Vice President, Admin Services

Fragmented Memories

Like the lives of many Vietnamese during the mid to late 1970's, my early memories were fragmented. I remember floating at sea in a crowd of strangers.

I remember the taste of rice porridge with salt and the smell of vomit. I remember wondering why we left the neighborhood train tracks I played on and when we would return to them.

I am a refugee from Vietnam and part of the thousands of “boat people” who fled the oppression of the communist regime in search of a better life. After spending months at a Malaysian camp, I arrived in the U.S. at the age of four along with my parents, four siblings, and one yellow suitcase.

Growing Up in San Jose

I grew up in a rough part of San Jose trying hard to assimilate and shed my refugee status. At home, I improved my English skills by watching shows like Little House on the Prairie and reading from the World Book Encyclopedia, a purchase that my dad paid off in monthly installments. It was our version of the Internet and worth every penny. At school, I skipped classes and making friends to avoid being introduced by my birth name, Dũng (roughly pronounced “yoomng”). The name means bravery in Vietnam, but I didn’t always have the courage to carry such a name here in the U.S.

In middle school, I was placed in Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) and a summer performing arts program that exposed me to books, art, plays, and music that were not enjoyed in my household. Do you know that tired trope of the poor kid thrust into high society? That’s what it felt like – yet another culture that I didn’t belong to. But I had a nurturing music teacher who taught me about expression and creativity, helped me step out of my shell, and convinced me that I didn’t need to be the same to belong.

My immigrant double life continued in high school. I began to embrace my Vietnamese identity, which is to say I was recreating what it meant to be Vietnamese in America. I was navigating two sets of rules and did not know who or what I wanted to be.

In contrast, my older brother had it all figured out and was on the path to become an Andrew Hill High School valedictorian, Yale magna cum laude graduate, and UC San Diego medical student.

My path was toward recurring trouble, visits to the principal’s office, and three different schools. It took a caring math teacher to convince me of my potential and help me turn things around, and when I did, I worked hard at it. How could I not?

My parents sacrificed their lives for me. Their unconditional support and a few positive influences in my life kept me close enough on the path to make it to college.

First-Generation, Low-Income, Minority College Student

Many low-income, first-generation, and minority students doubt their ability to succeed in college and I was no different. I lived at home and worked multiple jobs, and this kept me from feeling like a college student and connecting with the campus. Given my rocky path in high school, I felt like a straight-up imposter at a university.

I thought I wanted to be an engineer because doctors, lawyers, and engineers were the admired professions I heard about growing up. I did not know about other majors, and without an Educational Plan, I was aimless. I picked only Tuesday and Thursday classes so I could work the other days.

I tried to get by without buying textbooks or parking permits because I wanted to save money and had no intention to stay on campus beyond what was required. Assembling electronics and delivering pizza were more straightforward to me than small-group discussions on the Rodney King verdict, so I chose to work instead of attend classes. And of course, I didn’t know to drop them.

I wish I had known how Counseling, advising, and tutoring services could have helped but wonder if I would have even asked for it. Anyway, I was placed on academic disqualification and took this as a sign that I did not belong there. I had already enrolled in a summer public speaking class and decided to go through with it.

The instructor took the time to learn about me, and our conversations and my success in that class gave me the confidence to continue (learning to accept criticism and overcoming the fear of public speaking really boosts one’s confidence!). This completely changed my outlook and once I set my sights on pharmacy school, I worked extra hard to get there.

My failures up to this point correlated with situations where I felt I did not belong and pretended not to care. When I felt connected, confident, and believed that I mattered, I succeeded. That is why I love Mission, and the sense of belonging here is important to me.

A Sense of Duty and Understanding

Right before starting pharmacy school, I lost my brother to suicide. Our family was devastated. I would come to learn that many of us suffered from mental illness but never talked about it. My brother was the pride of our family not only because of his accomplishments, but because he was the “đích tôn” – the oldest grandson of the first-born son (in our culture, family lineage passes through the paternal line). I was now left as the oldest son, but that paternal lineage didn’t matter to me.

What mattered to me was the duty and responsibility to my family. I wanted to quit school to be near them and care for them. My supporters convinced me that the best way to do this and to honor my brother was to complete my educational goal.

I set out to do this with a new sense of duty and a promise not to take life or anything else for granted. I had much more inner strength than I realized, and the renewed closeness with friends and family in the aftermath made me even stronger. I excelled in pharmacy school in all the ways I wished I could have done so in my undergraduate program.

I worked multiple jobs but picked those that further developed my skills and learned to prioritize my studies. I connected with my communities on and off campus and stepped out of my comfort zone to network, volunteer, tutor, and lead others. Who knew that being part of a community would be so critical to my success? Heck, who knew that surviving trauma could have such a positive effect?

Since my brother’s passing, I aspired to continually reorient my life toward more fulfilling goals. I didn’t consciously choose to leave pharmacy, but when opportunities arose, my choices led me toward education. Looking back, I see that I had failed and veered off the path numerous times. But with encouragement from teachers and supporters at pivotal moments, I had always chosen education as my way back.

I have reinvented myself many times over by learning from my failures and re-routing myself onto new paths towards my goals. My journey included the many typical educational paths: that of the immigrant student fighting to assimilate, the disgruntled student rebelling against cultural pressures and expectations, the driven student pursuing education as a means to a better life, and the lifelong student seeking continued career and personal growth. It doesn’t matter which path you are on and how you get there.

Choose education, work hard, believe in yourself, and you will get there.